Droughts - Adapt or Dry

The first part of a three-part article series on the ongoing drought in the Netherlands.

In this first part of a three-part article series I focus on the causes of the current ongoing drought in the Netherlands and much of Europe. In the other two articles I shall focus on the consequences of droughts and on what is being (and what can be) done about them.

Note: Some of the sources in this article are in Dutch. I have removed some Dutch sources from the original article, so that only those sources remain that I deemed too important to remove.

The last couple of months have been particularly dry in the Netherlands. The amount of water that the agricultural sector is allowed to use has been curbed in several regions, particularly in the more sandy south and east of the country. Grasslands are so arid that they can only be used for hay, and many waters are no longer safe for swimming due to the proliferation of toxic blue-green algae. When the Minister of Infrastructure and Water tells the Dutch that they should “think carefully” about washing their car or filling their inflatable pool, they know that the situation must be really serious — or not, as one news outlet found that almost half of the country’s citizens won’t change their behaviour.

Ever since the 3rd of August there has been a ‘factual water shortage’ in the Netherlands, which is one step above an ‘imminent water shortage’ (started on 13 July) but one step short of an ‘imminent national crisis’. A Management Team Water shortages (MTW) has been convened in order to ensure that the water distribution is properly managed, that access to drinking water is safeguarded, and that nature and dikes are not irreversibly damaged. This team consists of representatives from Rijkswaterstaat (Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management), water boards (regional governing bodies charged with the management of surface water), drinking water companies, provincial governments, and several ministries. The MTW has the authority to take regional or national measures, like the aforementioned curbing of agricultural water use. The image below shows the precipitation shortage (Dutch: neerslagtekort) in the Netherlands the past few months.

—> Here you can take a look at the historical record of precipitation shortages in the Netherlands of the past 20 years.

Why is this happening?

According to the head of the MTW Michèle Blom, the water shortage is caused by “a lot of evaporation” and a “very low river supply from abroad”. But why is this happening, and is this unusual?

Evaporation is a natural part of the water cycle. Whether we are talking about water in a river or lake, or about the water that is held by plants and trees, when it gets warmer a part of it will evaporate. The higher the temperature, the more water tends to evaporate. So when temperatures in much of Europe are as high as they have been this summer, then that also means that rivers contain less water. This summer around 43% of European soil is in ‘warning’ conditions and 21% in ‘alert’ conditions, according to the European Drought Observatory.

Another factor is the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. The Dutch meteorological institute (KNMI) has measured the “most solar radiation ever” this summer. That means even more evaporation and even less water.

The higher temperatures are partly the consequence of global warming, caused by the anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases. In the Netherlands it is now 1.5 - 2.7°C (Source: KNMI climate dashboard) warmer than it was at the start of the 20th century (compared to ~1°C globally). Solar radiation is also increasing, in part because of a decrease in cloud cover and better air quality. Besides higher temperatures, the warming is also resulting in unpredictable changes in weather patterns. One example of this is the catastrophic flooding currently occurring in Pakistan, with a staggering one-third of the entire country under water, which have followed eight weeks of heavy rainfall. The country also had to endure heat waves this summer, where temperatures exceeded 50°C. Global warming has made the heat wave 30 times more likely. When it is that hot, more rain will fall, not only because more water evaporates but also because hotter air can hold more moisture. That is one of the causes of the flooding that occurred in Germany and the Netherlands last year, also following heavy rainfall.

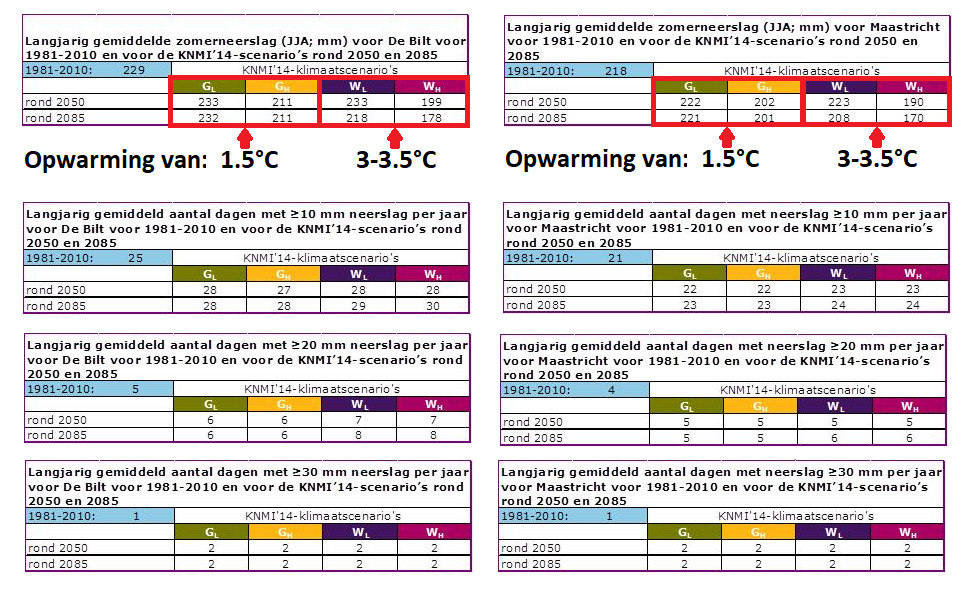

Since 1951, the number of days in the year with high rainfall (more than 50 mm) has increased by 70%. The amount of rainfall has also increased, mainly near the coast and close to cities (possibly due to the ‘heat island effect’ and particulate matter). But don’t forget, warmer temperatures means more moisture in the air. That means that it takes longer for rain to fall. Once it finally rains, it pours, resulting in more rainfall than the soil or sewer systems are able to take in. Moreover, these increases in rainfall amounts are occurring in the winter. In the spring, summer, and autumn rainfall amounts are actually decreasing (and so it raining less often and more intensely), which is causing problems in nature and with crop growth.

A recent study also found that summers in the Netherlands are getting drier. Heat increases in the south of Europe are causing more heat layers to rise up and push dry easterly winds towards the Netherlands, making the climate “drier” and “more continental” (it should be noted that these findings still contain large uncertainties).

Additionally, heat waves in the Netherlands are getting longer and more intense. This is related to changes occurring in the jet streams above Eurasia. An important cause of these changes is the fact that the land in the higher latitudes in warming at a much faster rate than the cold ocean around it, creating a stronger polar wind that makes the warmer air current stay above Europe for longer. Coincidentally, something similar happened in February 2021, only with cold air being trapped, giving the Netherlands a brief period of such intense cold that everyone could go ice skating on lakes and rivers.

Current climate pledges will, if they are kept, warm the world around 3°C by the end of the century. The consequences of so much warming will be enormous, with more deadly heat waves, long-lasting droughts, forest fires, and heavy rainfall. Large parts of the Netherlands could even disappear beneath the ocean. But there are still large uncertainties. We do not know how exactly the climate is going to respond to such high concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. On the one hand the consequences could be less horrific than we fear, on the other there are several tipping points in nature, like the permafrost in the polar regions, which could irreversibly melt. That would not only cause the sea level to rise, but would also release the potent greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere, resulting in rapid heating. Basically, you don’t really want to find out what does or does not happen in such a warm world. That is why for years scientists have been arguing for limiting global warming to 1.5°C, a goal that, if you look at the current political urgency, is still a long way off.

Do you want to support my work? With a donation you help me to keep producing content.