Dutch Election Shows Politics In Trouble

An Examination Of The Crises That Led To The Massive Victory of Geert Wilders' Anti-Immigration Freedom Party

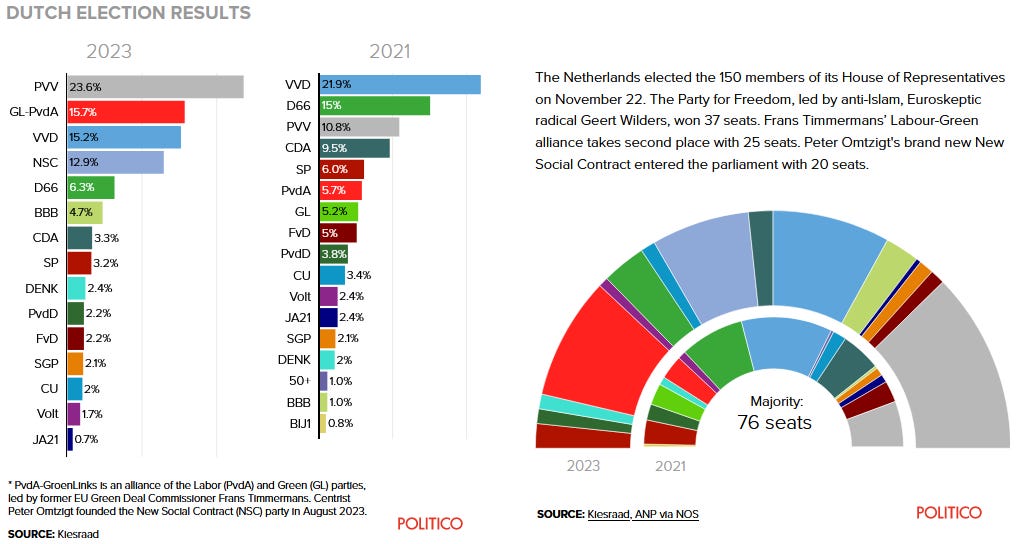

The recent Dutch election result was called “a stunning lurch to the far right for a nation once famed as a beacon of tolerance” (AP), “sending a chill across Europe” (the Guardian), “a wake-up call” (De Standaard) and “an outcome that could send shock waves through Europe” (New York Times). Seriously? Not that I'm claiming that I could have predicted the outcome, but is it really such a 'shocking' result? These headlines would have you believe that a lot of Dutch people have all of a sudden become staunchly anti-immigrant and decided that they want to be ruled by a strong leader to make their country great again. While those people definitely exist, as they do in many other countries, I do not think that that is why the Freedom Party won so many seats. They won so many seats because they give a voice to the widespread dissatisfaction with the government and its institutions, which is far from unjustified. Political commentators talk about how unexpected it all was, and how the polls did not show such a big lead for Geert Wilders’ party. I’m pretty sure I’ve heard this whole story before. Pollsters often miss precisely those people who feel left out of society.

So what’s wrong? Trust in the government is at its lowest in over a decade. Last year, 62% of Dutch people thought that the country was moving in the wrong direction, a 16% increase compared to the beginning of last year, with 73% expecting that the economy is going to worsen. There's been crisis after crisis, none of which have been adequately solved by politicians. In this election, government parties all lost seats, and the parties with the biggest gains are all promising to make radical changes to the current system or the current way of doing things.

It increasingly seems to me that all those political commentators' job is just to be perpetually wrong all the time. Feelings of shock and surprise only occur when your reality is abruptly changed by something that you did not see coming. This reaction is part of why I wanted to write a series of posts about these results, because I think that it would behoove us to drop the left/right lens, as it only obfuscates a much more complex reality that much better explains these results, as well as many other election results throughout the West.

This week, I will take a look at the crisis around gas drilling and the earthquakes this caused in the north of the country, which led to thousands of damaged homes, the childcare benefits scandal which caused the government before this last one to fall, as well as things like the effects of pandemic policy on public trust and the democratic process. Next week, you can read more about the nitrogen deposition crisis and subsequent farmer protests, as well as the housing and migrant crisis that were a huge part of this election. In the final article in this series, which will be published in a couple of weeks, I will share some of my opinions on the results as well as on the government formation process so far. Knowing the Dutch election process, it seems quite safe to assume that there won’t be a new government before then. My goal in writing this is not to provide a comprehensive or complete overview of these issues, which would take a whole separate post for each issue, but to illustrate the extent to which the Dutch political system is in crisis and add a perspective to the discussions around the results that I feel is lacking. I encourage you to share your own perspective or add to the points that I raise, as the nature of who won an election and why always includes a fair bit of speculation.

In this post as well as the next one, I will go through a few of these crises in no particular order, to give you an idea of the extent of what is in essence a series of structural problems that need to be addressed as soon as possible.

Note: because I talk about things happening in the Netherlands, most of the sources in these posts are in Dutch. Browsers like Chrome offer an automatic translate option that you can use to help you understand what the sources say.

CRISIS - Gas Drilling And Earthquakes

Decades of gas extraction have resulted in tremor damage to many people's houses in the northern province of Groningen. Insurance companies would not cover it, and the government-supported gas company NAM kept dragging its feet for years and years to compensate people for the damage. Even oil company Shell, who is a shareholder in the gas fields, did not want the drilling to continue (the Groningen gas fields are owned by ExxonMobil and Shell). Not because they were so concerned with the damage they were doing, of course, but because “the gains were getting too low and the costs too high”, or in other words, because the damages and lawsuits were becoming an ever bigger hassle. There have been months of parliamentary inquiries, which have been probing the exact nature of the partnership between the government and Shell and ExxonMobil. The long and short of it is that the government had a very cosy relationship with the fossil fuel companies, with Ben van Beurden, Shell CEO from 2014 to 2022, even seeing Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte as a “friend”. In short, economic interests superseded the well-being of the people of Groningen. And those concerns that Shell had that I mentioned? It seems that these concerns are related to a 2017 criminal lawsuit that was gaining traction in a Dutch court. The companies only wanted to continue drilling if the government took responsibility for the risks, which it did.

With ever more homes damaged by tremors, public outrage eventually reached a fever pitch, and in 2018 the government created an independent body to settle damage claims. To get a grip on the high number of damage compensation requests, people requesting compensation for the first time were automatically given 5,000 Euros, which was later increased to 10,000 Euros. The government is now going to start footing the bill for repairing damages of up to 60,000 Euros.

CRISIS - Childcare Benefits Scandal

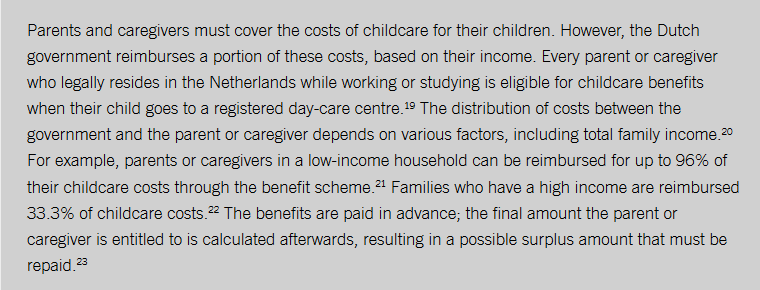

Thousands of parents receiving childcare benefits were accused of fraud, for things like making an error filling in a form. Tens of thousands more were labelled as fraudsters for mistakes in their tax returns. Using a risk assessment algorithm, the Dutch Tax Administration (‘Belastingdienst’) investigated people based on nationality, citizenship status, family ties, and living conditions. According to Dutch journalist Pieter Klein, internal emails show officials referring to people born in the Netherlands of Turkish parents as “Turks”, and using terms like a “nest of Antillians” and “blackies”.

Moreover, these algorithm-driven risk assessments created an “incentive to seize as many funds as possible, regardless of the accuracy of the accusations of fraud” in order “to cover the costs of the new methods”, summarises an Amnesty International report.

As a consequence, people had to pay back thousands of Euros that they often did not have and were, because of their alleged fraud, in many cases barred from paying the money back in instalments. People were driven into poverty and bankruptcy, evicted from their homes, and mental stress led to divorces and broken homes. When there was no longer any room under the rug from all its sweeping, the government’s response was a mix of denial, feigned ignorance, and spontaneous memory loss. To this day, when Dutch people don’t remember something they borrow prime minister Mark Rutte’s words and joke that they “do not have an active recollection of this".

It’s not just the Tax Administration, either. A few years ago, it was revealed that people on unemployment benefits were illegally investigated by the Unemployment Benefits agency UWV through IP address logging and tracking cookies that were linked to your Social Security number, In some cases people’s benefits were subsequently terminated based on this tracking. A judge recently declared that they have to pay everyone back in full.

CRISIS - Pandemic And Government Rule By Decree

During the pandemic, a handful of ministers were making national policy the likes of which has not been seen since World War 2, with very little or belated input from the national parliament. People had to prove vaccination status or negative Covid test results to get into restaurants and shops (except grocery stores), or were closed entirely, people were not allowed to go outside at night, schools were closed, protests were limited or forbidden, and the government created rules about how many people you were allowed to have over. While different countries had different policies, odds are you probably had similar personal experiences. Regardless of what you think of the proportionality or necessity of these policies, the main issue here is the fact that it was very difficult and in some cases almost impossible for the national parliament to provide the necessary democratic checks and balances in reaction to these policies. In short, what happened was that government ministers came together with a group of mostly unknown experts, decisions were made away from the public eye, a press conference was given in which the new rules were stipulated, and by the time there was a debate in parliament the government said it was too late to change the decision. Since the pandemic, trust in political institutions has, after a rise in 2020, declined to below pre-pandemic levels.

I’ll be going into more of the crises leading up to this election next week. Until then, feel free to leave a comment about the topics discussed in this post, I’m happy to engage you in a discussion about it. See you then!

UPDATE: You can find the follow-up post here:

Dutch Election Shows Politics In Trouble #2

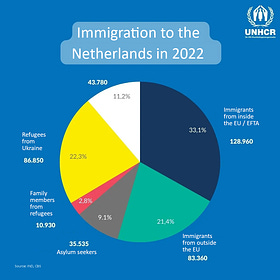

Last week, I talked about several crises that have been occurring in the Dutch political landscape over the past years. In this post, I am going to list several more, namely the nitrogen crisis, the ‘cost of living’ crisis in large part caused by the war in Ukraine, and a double crisis of migration and housing which may have played the largest role in the Freedom Party’s massive victory. If you have not already, read the previous post here:

Wonderful, fairly portrayed insights worth acknowledging. These insights could, as you mentioned/hinted at, be about any country. It's easy to take sides without attempting to understand the why? Glad you delved into that.