How the Dutch Government Regulates Online Content

A deep dive into publicly available documents and statements by public officials

Since the Digital Services Act was adopted in 2022, governments inside the European Union can ask companies to take down online illegal content, like child pornography, hate speech, scams, and material that promotes terrorism. Social media companies and other content providers are required to facilitate a standardised and swift way of removal. But who gets to decide when content is illegal, and how transparent are governments about how and what content they regulate? In this article, I use recent parliamentary debates, documents, and minutes to look into some of the ways in which the Dutch government and its agencies moderate online content.

A few years ago, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Dutch military was caught illegally monitoring and collecting information on Dutch citizens in order to fight disinformation around the COVID-19 pandemic, so that it could predict societal unrest. This was published in 2020 in an expose by Dutch newspaper NRC. (The article is paywalled, but coverage by other Dutch outlets can be found here and here. For an explanation in English, take a look at this study published in the European Journal of International Security.) This included building databases on Dutch anti-vaccination movements, but also other protest movements active in the Netherlands like the Yellow Vests, Qanon, 5G and Black Lives Matter. That incident demonstrates why government-mandated content moderation is such an important and contentious issue.

Online platforms can be used to instigate violence or self-harm, create disinformation, and affect people’s freedom to make informed political decisions, states the E.U.’s impact assessment of the Digital Services Act. When companies are left to decide what content to remove these decisions are usually “solely governed by the discretionary powers of the platform”, bringing with it risks to people’s freedom of expression. In cases where content is removed erroneously, this can then have “a chilling effect on the user’s freedom of expression”. Considering that these are the problems the E.U. regulation aims to solve, it should take extreme care not to create similar problems in the process.

That is why digital rights groups like non-profit Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) are worried by how the regulation could open the door to government overreach. The EFF is particularly alarmed by how the regulation gives government agencies the power to flag and remove potentially illegal content and to uncover data about anonymous speakers. They have also expressed concerns in the past about how government agencies can attain a ‘trusted flagger’ status, meaning that they get special privileges to ‘flag’ illegal content.

Removing content through an independent agency

On 7 June 2022, the European Union adopted a regulation that determined rules to “enable the swift removal of terrorist content”, which is defined as “material that incites or solicits an individual or a group of people to commit a terrorist act, or that provides instruction on making weapons or on other methods or techniques for use in a terrorist attack.” Excluded are materials that are published for “educational, journalistic, artistic, or research purposes” or for “preventing or countering terrorism”. Each member state is required to implement this regulation and to determine or create an authority that monitors content and where necessary gives sanctions and removal orders.

To this end, the Netherlands is implementing legislation that creates an agency dedicated to online terrorist content and child pornography (in Dutch: ‘Autoriteit Online Terroristisch en Kinderpornografisch Materiaal’, or ATKM). This agency will be the one enforcing the European regulation, once the Dutch senate ratifies the law. The regulation is already legally binding, however, and requires hosting services to facilitate removal orders in a quick and adequate manner. An explanatory document on the Dutch government’s website states that it is important that the enforcement of the regulation is done by an independent body, so that freedom of speech can be safeguarded and the designation of terrorist content made by a politically neutral entity. It should be noted that the document acknowledges the possibility that other E.U. governments can also mandate content removals. As of yet, it is difficult to know how the implementation of this E.U. regulation will turn out, at least until the agency starts operating. What we can take a look at, however, is the ways in which the Dutch government has up until this point approached content moderation and removal.

Trusted flagger

Let’s start with the use of a ‘trusted flagger’ status by government agencies, with which they can notify social media companies and other content providers of illegal content. What exactly do these agencies do with these privileges? Well, the government explained some of these actions in a response to questions from a member of parliament. Hanke Bruins Slot, the Dutch Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, claimed that her ministry uses its trusted flagger status with “great restraint” and “only around election time”, when there is a “suspicion of dis- or misinformation whose content affects the integrity of the electoral process”. She also states that the companies are free to use their own independent judgement when determining whether or not to delete, label, or otherwise act against the content. In other words, the ministry says that it does not force these companies to delete content.

The ministry claims to have used its trusted flagger status 4 times with Meta (parent company of Facebook), twice with Twitter, and zero times with Google. The first time was on 9 March 2021, where it alerted Meta to a video in which it was claimed that casting your vote also meant giving permission to get vaccinated for Covid-19. Meta responded by placing a warning label under the video.

The second time was on 17 March 2021, in response to a message circulating on Facebook and Twitter (this was second of the two times it has notified Twitter), that stated that if one was still unsure whether to vote for the Party for Freedom or for Forum for Democracy (both right-wing parties), they could colour two boxes on their voting ballot. This would invalidate the ballot. The ministry alerted Facebook to seven messages that had not received a fact-checking label.

The third and fourth time the ministry used its status were both to get a response from Meta to a municipality’s request that had not received a reply. On 18 November 2021, the ministry alerted them to a blocked link to a voter’s guide for the local election. On 9 March 2022, it notified them that the Instagram page of a municipal councillor as well as that of a local party were blocked. Meta’s response was to unblock the link and the accounts, without specifying why they had been blocked.

The first time the ministry notified Twitter was on 11 March 2021, to inquire after the blocked account of a municipality. Twitter explained that a problem with phone number verification was the reason for the blocked account. The second time was mentioned above, for which the ministry says it has not checked how Twitter responded.

In the case of the other authorities shown in the table at the beginning of this article, the Dutch Secretary of State for Kingdom Relations and Digitalisation, Alexandra van Huffelen, has stated during a parliamentary question hour that the Kansspelautoriteit submitted a total of 73 notifications, the Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets submitted 134, and that the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority does not know how many since they do not record the number of requests they do. Additionally, it is not clear whether or not Dutch intelligence services have a trusted flagger status, although minister Slot has promised to check if that is the case.

If the Dutch government’s claims are indeed true, then it uses its trusted flagger status sparingly and leaves the response up to the company in question, at least as far as the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations is concerned. However, what is missing is more information on how other government bodies use their trusted flagger status. Furthermore, it is unclear how exactly these alerts from the government are phrased and what kind of response they expect, whether implicitly or explicitly, from the social media company. As was seen in the recently published Twitter Files, governmental requests can quite readily be interpreted as more than just a request that the company can choose to ignore. From the published internal communications between Twitter and various U.S. government agencies, it became quite clear that there was an expectation of compliance and an increasing amount of pressure to obey the government’s ‘requests’.

Do you think this type of content is just as important as I do? Consider leaving a donation so that I can keep doing this kind of work.

Please also consider upgrading to a paid subscription to my Substack to support my work and get access to bonus content.

Content removal

Whether or not these requests by the Dutch government are indeed merely requests, is still up for debate, at least until the working method of the government and its effects are shared more transparently. What is clear, however, is that the use of their trusted flagger status to submit requests is different from situations in which government agencies directly order the removal of content. So when do Dutch authorities or administrative bodies use their trusted flagger status and when do they directly order content to be removed? Basically, the government answer is that it uses its trusted flagger status to flag online content, when it does not have the authority to force companies to remove said content. Only when content is demonstrably, i.e. provable to a judge, against the law, does it have the authority to give a removal order.

As stated at the beginning of this article, the independent administrative body ATKM shall be the one monitoring online content and giving removal orders when it comes to ‘terrorist’ and ‘child pornographic content’. The determination of what constitutes such content is also going to be made by the ATKM, guided by Dutch and E.U. laws.

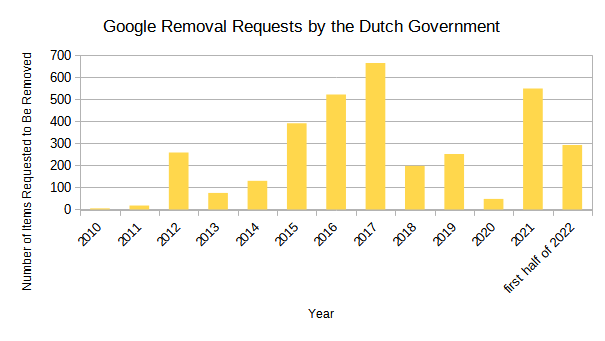

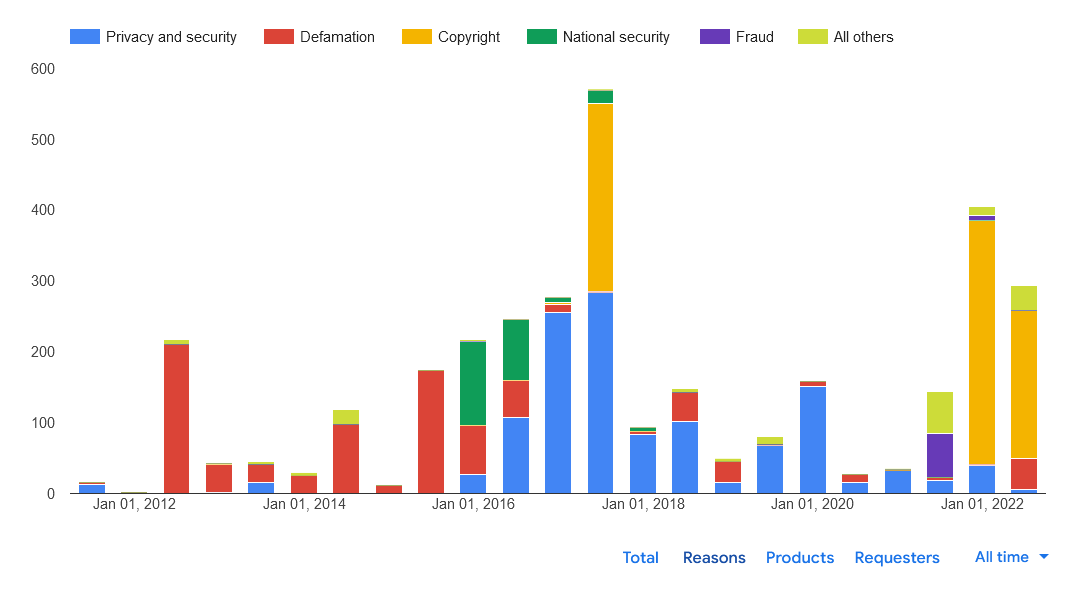

In other cases, it seems that government agencies either use their trusted flagger status, or simply notify content providers through conventional channels, to get content removed. To get an idea of how often content removals of all kinds are requested, take a look at the graphs below, which are based on Google’s Transparency Report. According to Google, this data is not comprehensive. Nevertheless, it is useful to observe general trends in the frequency and types of requests received. The data includes both mandatory and voluntary removal requests.

With regard to the Dutch police, minister Slot’s description of the extent to which it goes after online content was more broad. Apparently, the police can, “just like anyone else”, notify providers and platforms when they encounter expressions that go against their user policy, so that these can “judge these expressions based on the user policy”. When the content is deemed illegal, the police has, according to article 125p of the Dutch Criminal Procedure Code, the authority to order its removal, after permission from the judiciary. The Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority also has the authority to mandate the removal of content or even forcing websites offline to make sure that products or advertisements for products comply with E.U. health and safety regulations (2019/1020).

In summary, if the Dutch government’s explanations are true, then the Dutch government is not as heavily involved in regulating speech on the internet as the American government is, but there is nevertheless a general lack of oversight and transparent procedures regarding these requests and it is difficult to determine in what ways and which situations each authority makes them. The ways in which these kinds of laws and policies are implemented therefore remains something to pay close attention to.

Edited by Jayson Koch.