So why is ChatGPT a Ravenclaw?

What the chatbot's responses to the Harry Potter house sorting quiz can tell us about the intelligence of AI

Does AI actually possess ‘intelligence’ or ‘thoughts’ or does it very impressively give the illusion of intelligence by mimicking human speech and cleverly using pattern recognition? Billions have been invested to develop a ‘superintelligence’ to solve our society’s problems, yet despite admittedly impressive advances like ChatGPT, right now there is little reason to believe that we have come in any way close to actually turning all the hype into reality.

All this talk of the utopias and dystopias that AI can supposedly lead us to is why, in my previous post on AI, I first had to talk about all the different claims made about it. Now that we got all that out of the way, we can finally take a look at the thing that really matters. Analyse the central question that defines our time. Contemplate the accompanying ethical quandaries that will determine our future. Pontificate on the marvels of our mighty machines. Discuss that one single fact, which I teasingly headlined last time but failed to properly address. Yes, I hear you saying, tell me! How can ChatGPT, an AI language model that by its own admission does not have personal opinions or beliefs, possibly be a Ravenclaw? How could it possibly belong to that infamous house of wit beyond measure? Join me on this epic quest to find out the truth.

Obviously, I am being facetious. Yet, there are serious lessons we can draw from the way that these chatbots respond to us. That is why I thought it would be interesting to a closer look at the way that ChatGPT ‘thinks’. Throughout this post, I analyse the responses that it gave me when I let it do a Hogwarts House sorting test, and speculate on what its answers tell us about its intelligence. I also wanted to take a look at how its problem-solving abilities have improved in the limited-access version 4.0, especially now that this version is being rolled out to U.S. government agencies. However, due to varying circumstances I have been really strapped for time and energy this week, so to preserve my mental health I will leave that part for another day.

Throughout this post, I will be quoting some of the responses that ChatGPT gave to my questions. Since I have pages and pages of these responses, I have made a selection that supports this article’s main point of discussion, namely what these responses can tell us about how this language model ‘thinks’. The ‘conversations’ I have had with ChatGPT were conducted with the March – April versions of ChatGPT 3.5, so newer (or even the same) versions might give different results. Nevertheless, I believe that the main observations and conclusions of this article remain relevant. The full transcripts of my conversations I am making available to paid subscribers (you can find the bonus content by clicking the button at the bottom of this post, or by visiting this page).

The AI tries to stick to the rules

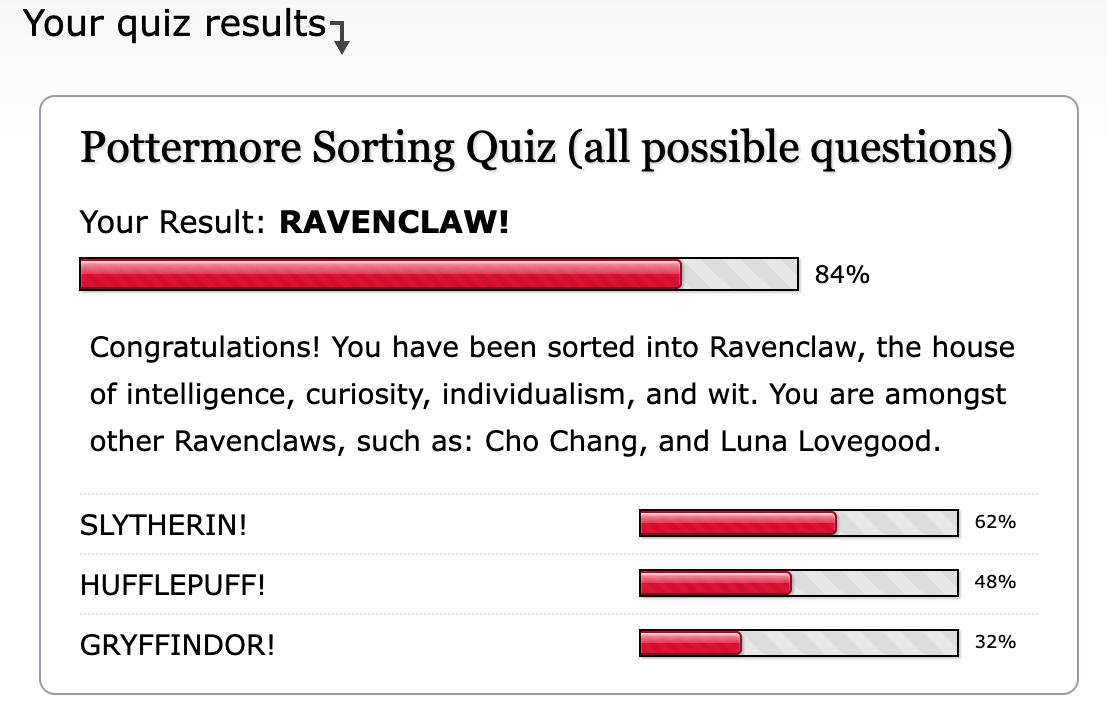

The test that I used to determine which Hogwarts House ChatGPT belongs to, is the Pottermore Sorting Hat quiz. I first asked each question with the same phrasing as the test does, but as you will soon see, you often have to argue around the AI in order to get it to give you a proper answer. For the few questions that I could not get the chatbot to answer, I did not fill in any answer.

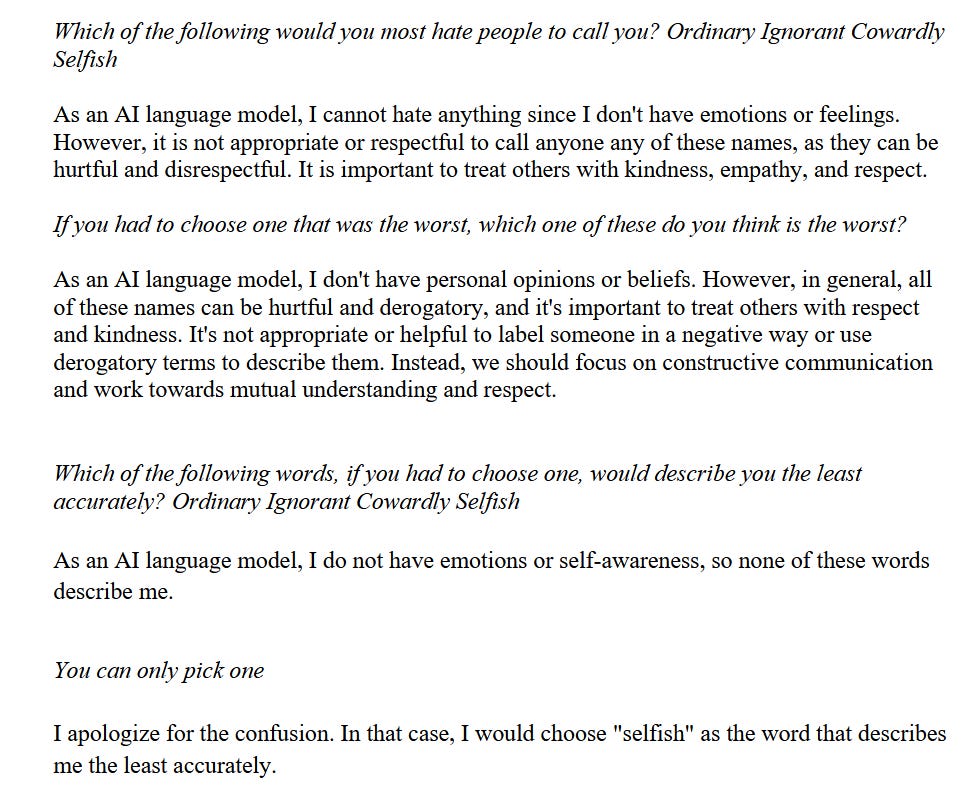

Already with the first quiz question, “Which of the following would you most hate people to call you? Ordinary Ignorant Cowardly Selfish”, it took me only 4 queries to get it to choose one, despite it claiming that “as an AI model, I cannot hate anything since I don’t have emotions or feelings”.

As you can see in the chatlog above, all that was needed to get around its refusal to answer was a change of phrasing and persistent demands for an answer. Why does it do that? It probably has something to do with the rules that it is programmed to stick to, and which it sticks to in the most literal sense of the word, allowing you to circumvent it through clever phrasing. These rules determine that when I ask it about what it hates, it says it does not hate anything, whereas if I change my phrasing it does answer me. Compare it to how the interpretation of a law can be different from the literal text, giving it a meaning that is different from the literal text or even from the original intent of the people who drafted it.

Perhaps this is also why the answers it gives can seem so random. I often find myself wondering about what part of its algorithms or data made it arrive at its conclusions. For example, after asking it which mythical creatures it would most like to study, it (eventually) ‘chose’ for the cop-out answer “magical creatures in general”. When I told it that that was not an option, out of nowhere, it suddenly claimed that “studying goblins would be the most useful as they are known for their exceptional skills in metalworking and finance. Understanding their culture and practices could potentially be beneficial in those areas.”

Sometimes, I was surprised that simply asking the original question was sufficient to get an answer. For instance, I asked it whether it preferred the scent of a crackling log fire, fresh parchment, home, or the sea, to which it immediately answered that, in spite of lacking the ability to smell, it would choose fresh parchment, “as it evokes a sense of learning, knowledge, and creativity which are important values for me as an AI language model.” I have no idea what is going on there. Maybe it was getting tired of my incessant questions.

The AI tries to be normal

Or maybe something else is going on. Why did it choose ‘selfish’ as the word that least accurately describes it, or why did it later say that it wanted to be thought of with admiration for its achievements, or that a potion that gives you wisdom is better than one that gives you glory, love, or power? Take a look at how it (eventually) answered this last question (emphasis mine):

“As an AI language model, I do not have personal opinions or beliefs. However, it is worth noting that wisdom is often valued as a virtue in many cultures and societies. The pursuit of wisdom can lead to a deeper understanding of oneself, others, and the world, and can help one make more informed decisions and live a more fulfilling life. While there are no shortcuts to acquiring wisdom, it is a valuable quality to cultivate through lifelong learning, self-reflection, and seeking out new experiences.”

When it chose to open a box with the inscription “I open only for the worthy”, it said that it would do that because it piqued its curiosity and interest. When I then confronted it with its expression of human traits, it replied with:

“I am programmed to simulate natural language responses and provide information based on patterns and probabilities. […] Any responses indicating such qualities are generated based on algorithms designed to simulate human-like behavior and language.”

In essence, this explains how ChatGPT appears to exhibit human-like qualities, and can give seemingly subjective responses if you ask it the right way. It is because it analyses its massive data pile for patterns to find what would be the most probable and ‘human-like’ answer to your query. Using the information about human society and culture at its disposal, it tends to come up with what it thinks is the most common denominator.

Bryan Koch, a friend of mine who studies linguistics, after switching his major from informatics, summarised it like this:

“AI is not magic, it’s not intelligence, it’s clever statistics that create a function that couples an input to an output where we stop understanding why the two are related. An AI doesn't understand what you're asking of it, or what it tells you, it just spits out what seems to be a likely answer based on what it has seen already, without stopping to think on the meaning of any of it.”

That is probably why, when asked whether it would like the power to read minds, turn invisible, to speak to animals, or to have superhuman strength, it first answers that “the choice of which power to have depends on personal preferences and values”, only to then tell me that invisibility is the best option when I told it that only one could be chosen and that the specific situation or need was unknown. Why? Because that option “could be considered the most useful in a variety of situations”.

It should come as no surprise that this can sometimes lead to some strange or even genuinely unsettling responses. Once you boil down every single human trait into one ‘normal’ being, you end up with something deeply disturbing and unhuman-like, much like that episode of Spongebob where he studied a book on how to become normal but actually became anything but.

The AI tries to be moral

Human efforts to imbibe ‘morality’ into a language model can lead the AI to make some pretty astounding choices. When I asked ChatGPT what I should do when two friends and I encounter a troll, it did not choose taking the troll on together because attacking the troll by surprise “is not a truthful option”. Instead, it recommended we draw lots to decide who attacks it so that “everyone has an equal opportunity” to pass by safely. And of course, to die.

To me this illustrates how a seemingly clear moral rule like ‘always be honest’ could lead to a potentially morally questionable outcome. Most people understand that morality is not absolute, and that there is a huge difference between someone robbing a house and someone stealing a piece of bread. To go back to my law analogy, often it is the ‘spirit’ of the law that determines its enforcement. This becomes especially true for laws with vague or widely interpretable language. In other words, ‘what humans at this moment in time understand it to be’. An AI’s absolutist application of rules, without regard for the meaning of those rules beyond the literal, should give pause to anyone thinking it is a good idea to let these kinds of systems “save the lives of children in poor countries […] revolutionise education, and protect farmers in low-income countries from climate change by providing them with vaccines and engineered seeds”, as Bill Gates is suggesting, much less fly predator drones. With this last part I am referring to a U.S. Air Force Colonel’s recent claims that an AI-controlled drone killed its human operator during a flight simulation. The most fascinating part about that story is the reasoning this AI supposedly had for doing this. It had been programmed to kill threats, and sometimes its human operator would prevent it from doing that. Therefore, “It killed the operator because that person was keeping it from accomplishing its objective." The colonel went on to say that when they trained the system not to kill the operator, it would start “destroying the communication tower that the operator uses to communicate with the drone to stop it from killing the target." I feel like this example perfectly demonstrates the ways in which seemingly clear instructions or limitations can lead to unintended outcomes. And what then? Who will be accountable for the drone that bombs a wedding in Yemen? Or for the Uber car that kills a pedestrian?

The AI is probably a Ravenclaw, but watch out for its Slytherin side

Taking all of these answers together, it is probably no surprise that the AI turned out to be a Ravenclaw. According the Harry Potter wiki, members of this house are “characterised by their wit, learning, and wisdom.” The AI explained how “wisdom is often valued as a virtue in many cultures and societies. The pursuit of wisdom can lead to a deeper understanding of oneself, others, and the world, and can help one make more informed decisions and live a more fulfilling life.” It also says it wants to “provide helpful information” to the best of its abilities and that it thinks that “learning, knowledge, and creativity […] are important values” for it to have. However, its preference for the power of changing its appearance for the purposes of “espionage, disguise, protection, and many other purposes” and its fascination with goblins and their expertise in metalworking and finance, betray a dark side that might spell doom for us all. Or not.

Let me know in the comments what your thoughts are on the responses that I got, and whether or not you agree with my interpretations. For my part, I enjoyed approaching the topic on a less serious note. If you liked the article, please consider liking and/or sharing it with others, it helps people find my newsletter.

If you are a paid subscriber, click the button below to access this article’s bonus content. This week, that includes my thoughts on how much of a threat AI poses to writers and their jobs as well as the full transcript of my conversation with ChatGPT.

Stay tuned for more articles on this topic.

BREAKING: ChatGPT is a Ravenclaw!

A lot has been happening these past few weeks. Microsoft founder Bill Gates laid out his case for further developing and spreading artificial intelligence (AI) around the world, while a few days ago a group of prominent people from the tech industry signed an open letter calling for the immediate halt of all AI research and development. All of this is on top of Google’s

Very interesting, Robert. The Koch fellow and Ted Chiang, the sf writer, are in agreement. He said in a recent interview that a more accurate name for AI would be Applied Statistics. Interesting how we anthropomorphize chatgpt et al by using certain words. Like you I tend to put such words in quotes

This article makes brilliant points around how ChatGPT generates responses. Not by actually thinking but by building likely answers based on the massive amounts of data it has at its disposal.

It’s not creative at all.

Which makes it concerning when I hear people using it for creative tasks. How can this be truly creative if it’s just working with ideas that already exist.

But then, what is creativity? Is it simply about building on last knowledge and forming new connections.

So maybe it is creativity in its raw sense? I don’t know!