Having Our Cake and Its Packaging Too

An ongoing investigation into microplastics and our current understanding of their possible harms

From the moment a plastic bag or piece of packaging is created, it begins to degrade as it comes into contact with air, light, liquids, and so on. As a result, minuscule plastic particles are released which find their way into our crops, soil, waterways, air, and bodies. You have probably heard many stories about plastic found on Mount Everest, at the bottom of the ocean, inside the bodies of marine animals and in those of humans, from our brains to our placentas and sperm. But how much of an issue is this, really? And how much do we actually know about the effects that these plastic particles have on our health, or on our ecosystems?

Over a series of posts, I intend to examine the different aspects of plastic pollution and give you an overview of the current state of this rapidly evolving field of scientific research. While plastic pollution in and of itself can be harmful to the environment, for instance when animals get stuck or mistake a piece of plastic for food, it’s the microscopic particles that we’ll primarily be looking at. Figuring out how to deal with plastic is a vital problem for humanity to figure out, which makes the topic a perfect fit for this newsletter. Plastic pollution can have lasting impacts for life on this planet and failing to address it could affect many aspects of our existence.

In this series of posts you can expect to learn more about the following aspects of plastic pollution:

What are micro/nanoplastics

Looking beyond the headlines – avoiding sensationalism in reporting on scientific research

Health risks of microplastics

Environmental consequences of microplastics

What can we do to address plastic pollution?

If you would like to directly support me in these efforts, which involves time-consuming activities like reading through piles of scientific studies, please consider leaving a donation using the button below or taking a paid subscription, which also provides you with access to the fiction stories I’m currently writing. Sharing these articles is also greatly appreciated, so that more people can learn about this topic.

What are micro/nanoplastics?

The tiny particles I mentioned in the introduction are often referred to as microplastics, and in some cases as nanoplastics. Since these words are going to get mentioned a lot in any discussion about plastic pollution, it is important to know what exactly is meant with these terms.

In short, microplastics are solid plastic particles that are up to 5 millimeters in size, while nanoplastics are defined as plastic particles that are smaller than 1 micrometer and therefore invisible to the naked eye. Although the word microplastics is quite often used as a kind of catch-all term, referring to all manner of tiny plastic particles, the crucial difference is that nanoplastics are so small that they are able to enter cells and tissues. For ease of discussion, I’ll be using the abbreviation MNP (Micro- and Nanoplastic Particles) to refer to both. If I use the term microplastics instead of MNP, that is a deliberate decision for sake of accuracy. Many studies have only examined microplastics, and their conclusions therefore might not apply to nanoplastics.

Here is an image to help you better visualize the sizes of MNP:

Where are all these microplastic particles coming from?

Plastic is everywhere, which means we are exposed to MNP everywhere we go. Let us take a look at some of the major sources of MNP exposure.

We can divide sources of MNP into two categories: primary and secondary sources. Primary sources are manufactured microplastics that are put into cosmetics or paints, or that are used directly as small pieces—you know, like those glitter particles that get everywhere—or that serve as the base materials for plastic products (look up ‘nurdles’, a term which for me conjures up images of mischievous goblins but when I looked it up turned out to refer to something much more sinister). Secondary sources are those referred to at the beginning of this article, the MNP that are generated as larger items break down in the environment or are recycled, or when you put polyester clothing into your washing machine (a 5-kg load of polyester can release up to 6 million microfibers into the water).

Six key sources of microplastics are macroplastic (larger plastic items; about 7,568 kilotonnes of microplastics are estimated to leak from them into the ocean each year), paint (1,301 kt/y), tires (973 kt/y), plastic pallets (like nurdles; 254 kt/y), synthetic textiles (211 kt/y), and personal care products (57 kt/y). The total emissions of microplastics into the environment are estimated to amount to about 10-40 million tonnes per year, and could double by 2040 if we proceed with business as usual.

While our own exposure is bound to be highly dependent on where and how we live, it appears that one of the biggest sources of microplastics exposure for humans is not seafood or the packaging around our food, but the air itself. That would seem to suggest that the best thing you can do to limit your exposure to MNP is to ensure good ventilation when you are inside, which has many other health benefits beside, like reducing your exposure to pathogens and pollutants. We’ll be taking a closer look at other sources of exposure in the post that will look at the possible health risks of microplastics.

What are MNP made of?

This is the final aspect that is important to discuss before we can dive deeper into the subject. To understand what MNP are made of, and therefore to be able to understand the possible risks that they could pose, we should be aware of two aspects of their make-up.

First, there is the obvious aspect, the plastic itself. So what is plastic? Plastics are ‘synthetic polymers’. A polymer is a large molecule made up of many different segments (poly=many, mer=segments/parts). It is called synthetic because it was made by humans, as opposed to natural polymers like silk, rubber, or DNA.

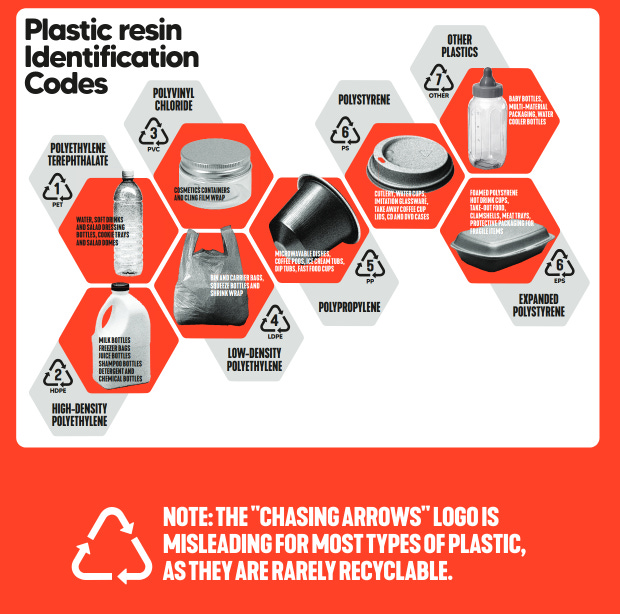

There are many different kinds of plastics in use, but conventional plastics (so excluding bio-based plastics, for which see the information box further down in this section) tend to be mostly made out of hydrocarbons, which means that their long molecule chains consist of water and carbon atoms. Some of the most common plastic materials are polypropylene (bottle caps, adhesive tape, coffee pods), polyethylene (plastic bottles, polyester clothing, lining in milk cartons), PVC (credit cards, air/water circulation pipes, healthcare items like blood bags), polystyrene (Styrofoam, yogurt cups), and polyurethane (furniture foam, thermal insulation, coat finish for floor/furniture).

To make plastics ready for whatever purpose they are meant to serve, all kinds of chemicals are added to these synthetic polymers to give them desirable properties, like being softer, durable, or fire-resistant. When plastics break down into the environment, for instance because of sunlight or contact with water, these chemicals can get released. Moreover, most additives are not chemically bound to plastic’s polymer chains, which means they can get released into their environment during the use, handling, and recycling processes of plastics.

More than 13,000 chemicals have so far been associated with plastics, according to a 2022 UN report. Some of these have become a subject of discussion over the last couple of years because of their potential to cause disease, like bisphenol A (BPA) and PFAS, but the truth is that we have very little idea of what all these different combinations of chemicals do once they get into our bodies or into the environment. So far we know of more than 3,200 with “one or more hazardous properties” like accumulating in the body, affecting hormones, reducing fertility, and/or causing nervous system damage or cancer. We will take a closer look at the possible health effects of MNP another time.

What about bio/plant-based/biodegradable plastics?

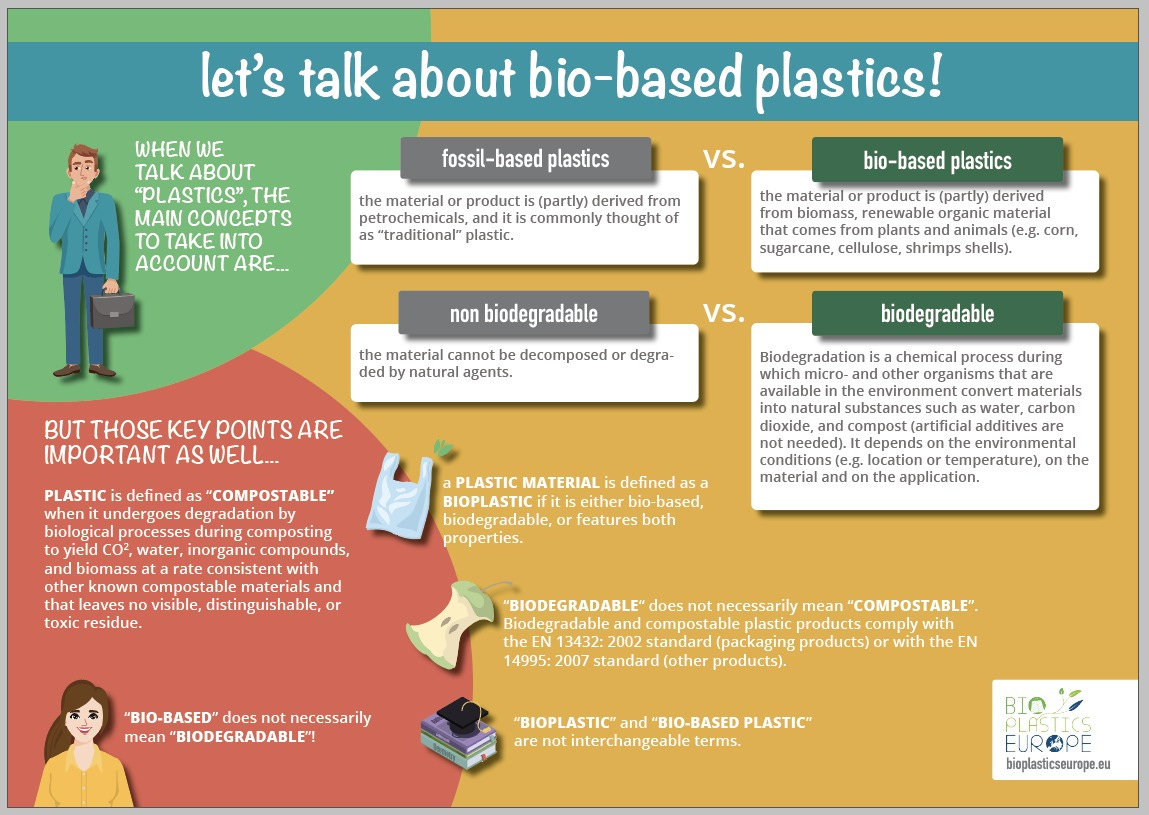

Bio-/plant-based plastics are in many ways similar to conventional plastics, only instead of fossil fuels they are made out of organic materials like sugarcane or corn. However, similar to conventional plastics, they often do not fully degrade in the environment and, just like with conventional plastics, harmful chemicals are often added during production. Bio-based plastics could reduce the reliance on fossil fuels for plastics production, but that fully depends on how they are produced and where the biomass used for their production comes from, as its production could still require the use of fossil fuels or the cutting down of forests for crops.

Biodegradable plastics are, by definition, plastics that can fully degrade in the environment within a reasonable amount of time (although how well depends on the environment). There exist both bio-based plastics and plastics made out of fossil fuels that are biodegradable. In other words, biodegradable does not refer to the materials the plastics are made out of, and how sustainable or 'green' those are, but their capacity to fully degrade and not persist in the environment. It is important to note that many products advertised as biodegradable are in reality compostable, meaning that they can biodegrade in industrial composting processes. When compostable plastics enter the environment, there’s a good chance they will not fully biodegrade and cause similar problems as regular plastics.

These different terms can be quite confusing, which is why I wanted to clarify them separately from the discussion above. These confusing terms are probably also why they are frequently used by companies to pretend their products and packaging are more sustainable than they actually are.Lastly, now that we have discussed the elements that go into plastics and that therefore are also in MNP, there is still the other, less discussed part to MNP left to talk about, namely the fact that they can be carriers for other things that could, just like the particles themselves and the chemicals that they release, disrupt ecosystems and our bodies. When MNP get into contact with the environment, they can adsorb (=particles stick to their surface) organic pollutants like waste, pesticides, dyes, and antibiotics, as well as pathogens and heavy metals like lead. These could therefore find their way into our bodies or into ecosystems. The concentrations of these chemicals leaching into our bodies out of microplastics particles may very well be negligible compared to the chemicals that we already ingest through our diet, at least for some of them, suggests one study that simulated microplastic chemical leaching for four chemicals, but that might not be the case for heavy metals like lead or if MNP accumulate locally, like in our liver or spleen. We will take a closer look at this ‘carrier’ aspect in the upcoming articles on health effects and environmental effects.

Final words (for now)

There’s a lot more to say about this complex subject and there remain many gaps in our understanding for scientists to study and better understand. Addressing plastic pollution remains one of the fundamental questions of our time, and unfortunately there remain many gaps in our understanding about the extent to which micro- and nanoplastics can be harmful.

The complex nature of the subject necessitates that I summarize and condense the information as much as possible. That means that some aspects of the topic may only be briefly touched upon, so feel free to ask me follow-up questions if there is anything you would like to know more about.

Thank you for covering this topic! I know I'm always confused why our recycling company won't take certain plastics over others. I really wish we could go back to glass and paper packages.