Replace all meat with plants. Problem solved. Right?

An ongoing look at what the effects are of shifting from meat to plant-based alternatives

Replacing the animal products in your diet with more plant-based alternatives is often touted as a way to reduce your impact on the environment and improve your health. But how sustainable are these alternatives really, and how much impact does a change in diet really have? In this article, we will compare the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of several different types of food, and consider how much our food decisions affect our environment.

I got interested to dive back into the topic after reading an article from

. The overall conclusion was that consuming meat substitutes instead of meat has a positive impact on the environment, for instance because its production causes fewer GHG emissions. There are two main aspects to this claim. Firstly, that eating meat substitutes is better for the environment than eating meat. Secondly, that changing your diet to include more (or only) plants has a positive impact on the environment. The first of these two aspects is what we are mainly looking at now, the second is a topic for another day.Food and greenhouse gas emissions

Let’s begin with an introduction to the connection between food and greenhouse gas emissions. Food production is responsible for around a quarter of the world’s GHG emissions. That makes it a much bigger source of emissions than, say, the entire transport sector (~16%) or the energy used for heating homes (~11%). In fact, without changing the way we produce and consume food, it is seen as unlikely that global warming can be limited to 2°C or less, a temperature rise that would already jeopardise the Earth’s ability to maintain conditions favourable to human life.

This year’s extreme weather events, from catastrophic droughts to unprecedented floodings, are a clear indicator that global warming is already leading to major problems all around the world. What is perhaps less known, is that food production is already 21% lower because of climate change. I must add, as I mentioned in this article on the consequences of droughts, that these losses are more than offset by the staggering gains in food production that humanity has managed to make the past century or so. However, the more the world warms, the larger these losses in yields are going to get. All the more reason to take seriously anything that might help in lowering carbon emissions. Take a look at the figure below, which lists all the different sectors where emissions could be reduced from now until 2030, and how big those reductions might be. The largest emission reductions can be achieved in energy generation, reduced clearing of forests and other ecosystems (usually for food production), and changing agricultural practices. Nevertheless, changing our diets can contribute significantly to achieving emission targets.

The numbers

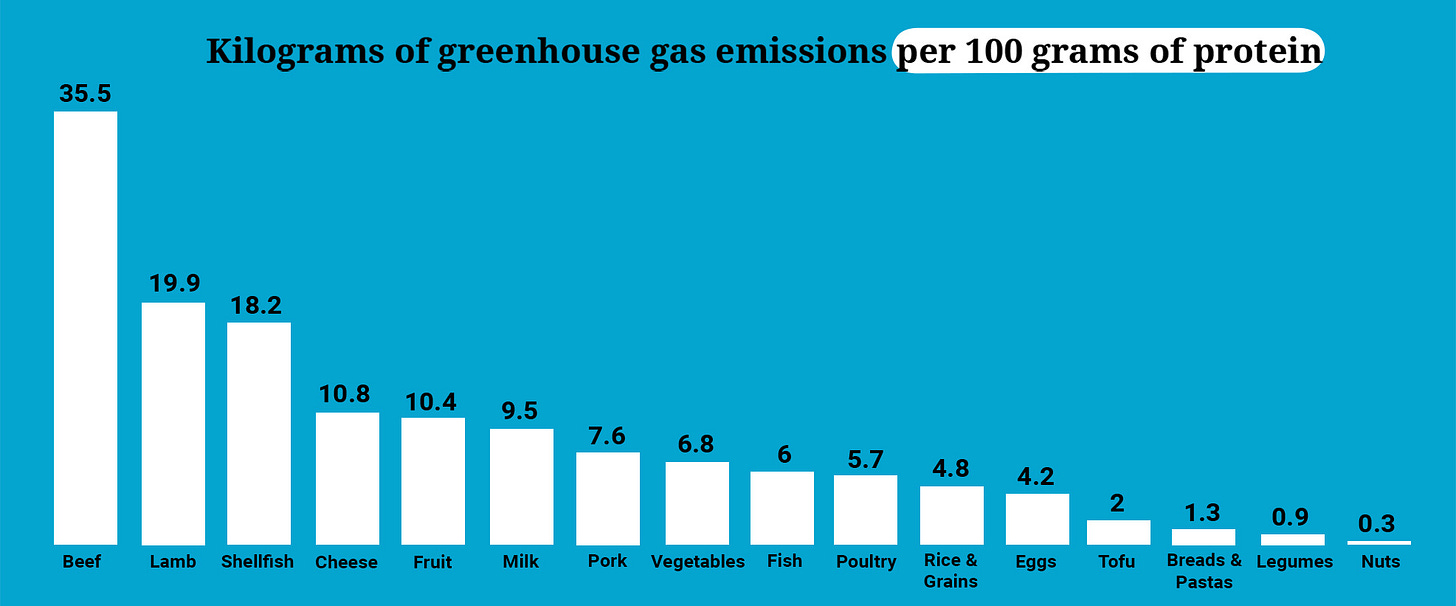

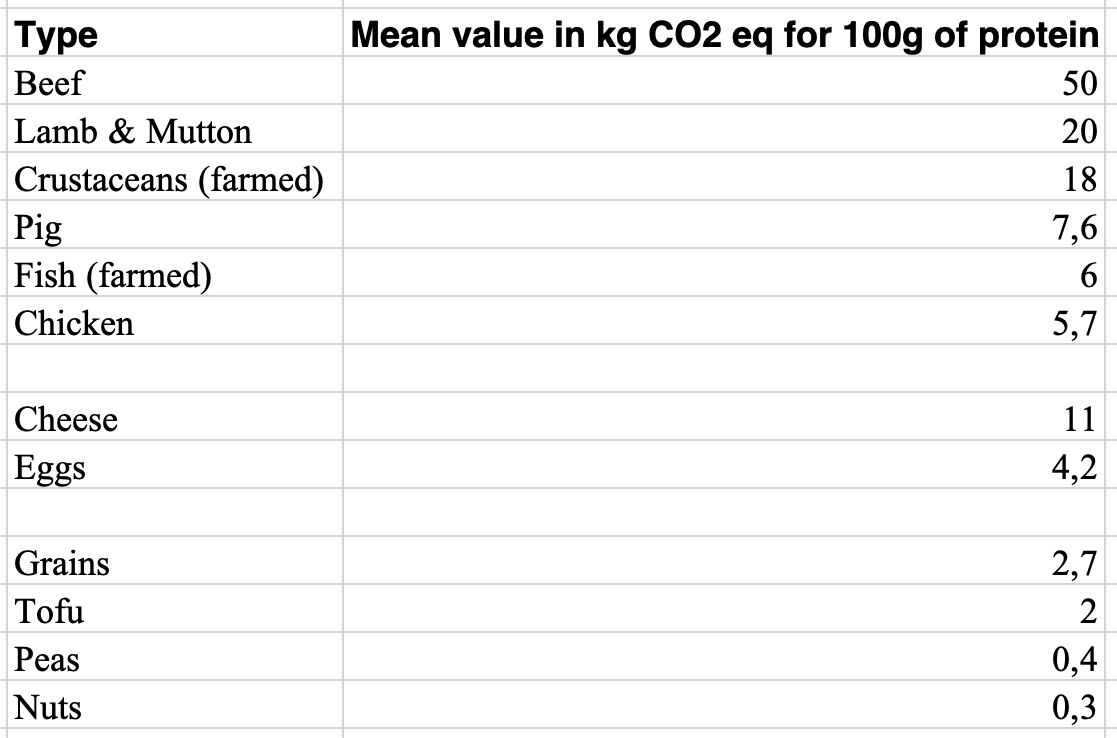

Let’s take a look at the foods that result in the most emissions. I found a study published in Science whose authors have analysed hundreds of different studies and calculated the mean GHG emissions associated with the production (so excluding transport, packaging etc.) of different types of food. What immediately becomes clear is that the production of beef causes a lot more emissions than, say, chicken.

Let’s compare these numbers to a meat alternative like the Beyond Meat burger. According to their self-commissioned Life Cycle Assessment conducted by the University of Michigan, a Beyond Burger causes 0.4 kg CO2 eq. of emissions for one 4 oz (113g) patty. My local supermarket sells this burger, and they have the same weight. According to the product description on the packaging, there is 17 g of protein contained in 100 g of burger. That means that to get 100 g of protein, you need about 6 (100/17=5.88) burgers. 6 burgers means 6 x 0.4 kg CO2 eq. of emissions = 2.4 kg. However, this does not only include production, but also packaging, processing, waste management, and so on. The ingredients themselves account for about 58% of total GHG emissions, according to the Life Cycle Assessment, which brings the emissions caused by the burger’s production to 1.4 kg. That means that, if we are only taking GHG emissions into account (we will look at other factors in the future), this burger would probably be a preferable choice over all other meats, as well as cheese and eggs. We will get more into the other factors, which are not all good, in a future article.

Want to take a look at the emissions caused by your diet? The BBC made this handy tool, based on the same study whose numbers we just looked at.

Role of behaviour often overlooked

According to the IPCC, food-related GHG emissions can be reduced by implementing better agricultural practices, conserving and strengthening nature, cutting down food waste, and, as mentioned earlier, changing your diet. However, that does not mean that changing your diet always leads to lower GHG emissions. One study assessed the effects of a combination of emission reduction practices on future greenhouse gas emissions. The researchers concluded that the effects of dietary changes on future emissions are much lower than the effects of other changes like implementing ‘low-emission practices’ that improve production efficiency and nature-based carbon sequestering (restoration of land that stores instead of emits greenhouse gases, like forests, peatlands etc.). Only when animal-based protein consumption was reduced by 25% or more, would it have an effect on future emissions (or 10-25% if accompanied by low-emission practices).

In other words, there is a case to be made against merely changing one aspect of our lives, whether it is our diet or our energy consumption. Especially because savings in one area could be offset by other behaviour. Another study found that if the average Swedish consumer were to shift to a vegetarian diet, which could save 16% of energy consumption (and therefore money) and 20% of their GHG emissions, these savings would be offset by respectively 96% and 49%, because they would spend the money they saved on products or activities that cause GHG emissions.

Looking forward

Next month, we will continue this analysis of the possible risks and benefits of exchanging meat for plant-based alternatives. Among other things, we will be looking at how different types of food affect land use, water, as well as our health.

Before you go, I would like to have your opinion as reader of Critical Consent. Normally, I would publish articles like these in a longer format, so that we can get into the nitty-gritty of a topic and get to grips with its nuances. However, I realise that you may not always have the time to completely read long posts, just like I sometimes have to really fight for time to write for you, as I talked about at length here. Therefore, I want to try out publishing these longer articles as part of a series, like I did with last year’s articles on droughts (the last part is still coming at some point). This reduces pressures on me, and potentially frees up more time for you to read my content. Let me know what you think about this change:

In any case, I hope you learned something from today’s post. Let me know what you think in the comments. Please consider liking and sharing this post so that more people can find my content.

Note: The post was mistakenly not sent by email upon publication. On 21 March, it was sent to subscribers, but that is why the publication date shows March 19.

I've found that a lot of analysis of beef and CO2 production revolves around factory farms and not sustainable farming. Cattle raised primarily on grassland emit greenhouse gasses that are then taken up by the grassland. There were literally millions of buffalo roaming this country 200 years ago. They fed off and fertilized grasslands. Would have been nice to analyze that cycle. I'm guessing there wasn't a lot of excess carbon going into the atmosphere.