Where we're going, we don't need roads

What H.G. Wells' the Time Machine can teach us about the future

There are days where I wonder where it is all going. With our governments increasingly preoccupied with controlling what can and cannot be said online, all signs pointing to (another) financial crisis looming on the horizon, the Ukraine war still escalating with each passing week, potentially towards fatal disaster, and people all around struggling to make ends meet and to simply live their lives. Why is it that despite our society’s many technological marvels, ever-growing knowledge, and historically unprecedented possibilities, we all live in a world of seeming perpetual conflict and crisis? How do we live our lives in a society that is barely fulfilling our psychological and spiritual needs as human beings? Would we not rather escape to a better, more enlightened time, away from this polarisation and division? That is exactly what the protagonist of H.G. Wells’ classic novella the Time Machine decided to do. Join me on a journey through time, as we explore what lessons we can draw from this 19th century book, for the present as well as for the future. The story also has firm roots in the theory of social Darwinism, which Sam W., writer of World-Weary Writer by Sam W, shall be explaining a little more about.

The plot

Let me first make sure you are not completely lost, by briefly explaining what the plot of the Time Machine revolves around. In the story, a scientist, who in enigmatic fashion is solely referred to as ‘the Time Traveller’, builds a time machine so that he can see all that humanity would accomplish in the future. However, instead of finding unparalleled scientific progress and enlightenment, what he finds instead is humanity in its sunset. The people that he first meets, the Eloi, live in blissful ignorance of the past, of all of humanity’s greatest accomplishments and struggles for freedom. Free from danger, free from struggle, they had devolved into “childish simplicity”, as there was no longer any need for those admirable human traits of intelligence or courage. However, it does not take long for the Time Traveller to find out that this is not the whole picture. Below ground, there lives another race of human descendants, the Morlocks, a feral species that cannot stand the light and sustains itself by consuming the Eloi. More on the fascinating history behind these two directions that human evolution takes later. Ultimately, the story raises questions about where civilisation’s endless pursuit of comfort will take us, and whether human dreams of progress and permanence are nothing but fleeting folly.

Evolution, eugenics, and the future of humanity

Let’s talk about the central theme of the story. In the year '“Eight Hundred and Two Thousand Seven Hundred and One”, the human species has evolved (or devolved depending on your perspective) into two distinct species. To understand what idea Wells, the author of the Time Machine, wanted to express with this unexpected turn of events, we first have to talk about eugenics.

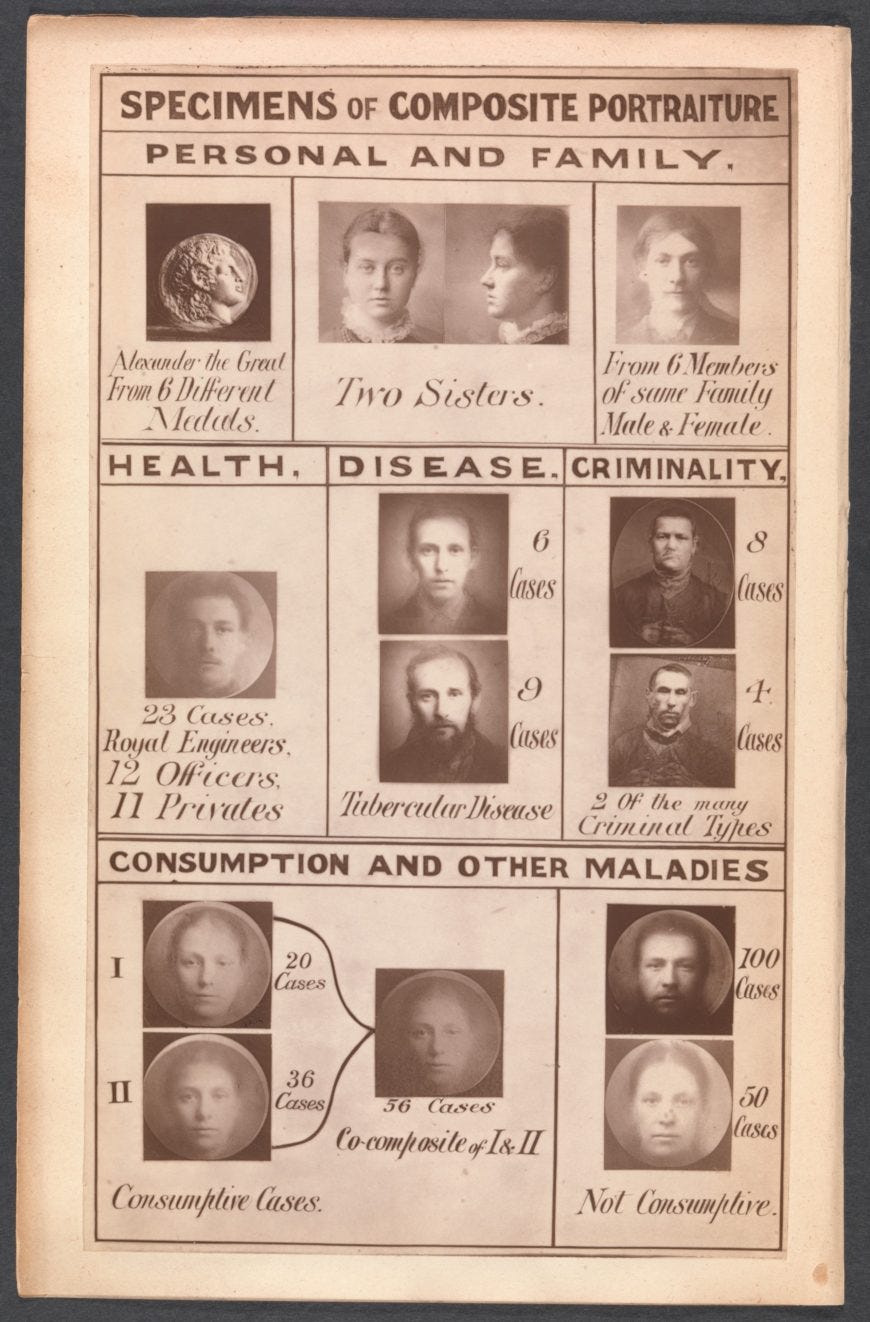

Eugenics is a by-product of the 19th century discovery of evolution by Charles Darwin. The (pseudo)science of eugenics aims to create a perfect society through selective breeding and controlled evolution. Basically, to make sure desirable traits are inherited by the next generation, and undesirable traits weeded out. The word is derived from the Greek word eugenes which means ‘good in birth’. Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin, believed that only higher races could be successful and that therefore only those people who possessed desirable hereditary traits should be passing on their genes to their children. On the other hand, people with undesirable traits like mental or physical disability, homosexuality, or criminality, should not be passing on their genes and thereby worsening the ‘common stock’. The theory of eugenics ultimately culminated in the Nazi’s ideology of a ‘master race’ whose ‘superior qualities’ had to be safeguarded from mixing with ‘inferior races’, so that it could become a ‘super race’.

Just this week, Sam W. of

wrote a comprehensive article about the history of the eugenics movement and its proponents. That is why I asked her to share some of her thoughts on the relationship between the theory of eugenics and the Time Machine. “Today, we are rightly horrified by the notion that human beings can be split up into ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’ on the basis of demographic,” she tells me, “but in the late 1800s through the early 1900s, this was not a radical notion at all.” Sam goes on to explain that eugenics has its roots in the theory of social Darwinism, which is itself an offshoot of Darwin’s theory of evolution: “The idea was that, through adversity, human beings would adapt to succeed. Social Darwinism is predicated upon the idea of rugged individualism; that every individual of the human species should be out for himself. It’s up to every individual man to sink or swim. Social Darwinists thought that success was proof of intelligence and strength, and that removing adversity and challenge would lead to laziness and a lack of motivation in the population. This idea shows up in the cult following of figures like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk; they’re rich, so they must be intelligent. It’s ironic, then, that Charles Darwin believed that cooperation, not individualism, was among the most beneficial traits a species can exhibit.”As I found out from reading Wells’ thoughts on the matter, he appears to not have been convinced by Galton’s ideas about eugenics, but instead maintained that “our analysis of human faculties is entirely inadequate for the purpose of tracing hereditary influence”. Moreover, Wells was “inclined to believe that a large proportion of our present-day criminals”, who Galton claimed should not be allowed to breed, were not only the “brightest and boldest members of families living under impossible conditions”, but that the average criminal was “in many desirable qualities” above the average law-abiding citizen and even the average judge. Why did he think this?

“Not out of the idea that it was ethically wrong to do so,” says Sam, “but because he felt that poverty-stricken people who turned to crime were embodying the ideal of social Darwinism. The Time Machine is an example of social Darwinism. Of the two subgroups of human descendants, the descendants of those who did not experience adversity were the ones who became weak, frail, and stupid. To Wells, removing adversity removed the motivation for the individual to succeed.”

That is what makes the divergence of human evolution described in the Time Machine so fascinating, because in the context of that time period it can be understood as a criticism of eugenics and an approval of social Darwinism. Take this fragment from the book, for instance:

“Again, the exclusive tendency of richer people […] is already leading to the closing, in their interest, of considerable portions of the surface of the land. About London, for instance, perhaps half the prettier country is shut in against intrusion. […] So, in the end, above ground you must have the Haves, pursuing pleasure and comfort and beauty, and below ground the Have-nots, the Workers getting continually adapted to the conditions of their labour. […] The great triumph of Humanity I had dreamed of took a different shape in my mind. It had been no such triumph of moral education and general co-operation as I had imagined. Instead, I saw a real aristocracy, armed with a perfected science and working to a logical conclusion the industrial system of today. Its triumph had not been simply a triumph over Nature, but a triumph over Nature and the fellow-man. […] the balanced civilisation that was at last attained must have long since passed its zenith, and was now far fallen into decay. The too-perfect security of the Overworlders had led them to a slow movement of degeneration, to a general dwindling in size, strength, and intelligence.”

Fragment has been shortened for clarity. You can find the full passage in Chapter 8.

In other words, instead of the “gradual widening” of the separation between the “Capitalist and the Labourer” leading to a superior race, it led to two races. One was a race of “beautiful people” who lived in “childish simplicity” and with mental feebleness, and the other was an “inhuman and malign” race of “ant-like” creatures, who kept and ate them as “fatted cattle”. Through the civilising process, the “dream of the human intellect” had “committed suicide”, by solving every social issue and setting itself “towards comfort and ease”. By creating a perfect harmony with its environment, humanity had thus eliminated the need for intelligence altogether: “Nature never appeals to intelligence until habit and instinct are useless. There is no intelligence where there is no change and no need of change.”

Now I don’t think we need to worry about humanity creating a perfect harmony with its environment any time soon, as the planet and its oceans heat up ever further and species go extinct at alarming rates, but the idea of the human species amusing itself to death is as relevant as it has ever been, with smartphones, social media, streaming services and their never-ending stream of content, notifications, and advertisements demanding every last bit of your attention (and sanity). Is it not true that, even more so after COVID-19, just like the “East-end worker” from Wells’ time, most of us “live in such artificial conditions as practically to be cut off from the natural surface of the earth?”

As I leave you to ponder all the questions raised in this post, let me finish with a hopeful quote from the book’s epilogue, which might give you solace and the resolve to never give up as it does me:

“He […] thought but cheerlessly of the Advancement of Mankind, and saw in the growing pile of civilisation only a foolish heaping that must inevitably fall back upon and destroy its makers in the end. If that is so, it remains for us to live as though it were not so. […] And I have by me, for my comfort, two strange white flowers—shrivelled now, and brown and flat and brittle—to witness that even when mind and strength had gone, gratitude and a mutual tenderness still lived on in the heart of man.”

If you want to learn more about the history of eugenics as well as more recent examples, I highly recommend you read Sam’s article.

If you are a paid subscriber, I have so many more fascinating things for you to read, as this is a topic that I kept finding more and more about, but which was too much to all fit inside the above post. Click here or on the button below for an analysis of several more fascinating aspects of the Time Machine; how it contrasts scientific optimism with Victorian pessimism, as well how it was influenced by Victorian gender ideology. On top of that, I also discuss the 1960 film, which adapted the story to warn about the futility of war and how it could also lead the dream of the human intellect to commit suicide, and I reminisce a little on why this story means so much to me.

Strong piece! Looking forward to your guest post!

It was great to have the chance to work with you on this one, Robert! Doing the research for it was really fun...in an 'oh wow, this is a horrifying belief system' kind of way.