💭 Prelude:

This is the second post of an ongoing collaboration series between Tony Ziade, the writer behind ShieldMe and Robert Urbaschek of Critical Consent. Together, we are exploring the intersection of technology and politics, along with other engaging topics that we believe will captivate our shared audience. You can find the last post here in case you missed it. Don't forget to like these posts and subscribe to Tony’s channel and to mine to show your support for our shared efforts!

Introduction:

Up until now, we have been looking at how microtargeting works and is used to analyze your data in order to influence you. But how effective is it actually as a means of manipulating your behavior? There is not a whole lot of information out there that can tell us something concrete about the results. For instance, no one really seems to know how much the Cambridge Analytica data influenced the Brexit referendum and the 2016 U.S. presidential election. It seems likely that it had some influence, but is the effect larger than, say, the effect of the countless of other ads on people's voting decisions, or of the state of the economy at the time? A big part of why these questions are so difficult to answer is the lack of transparency around how and by whom the data collected about you is used. That makes it incredibly difficult to know how and to what degree the information about us shapes our social media feeds and search results.

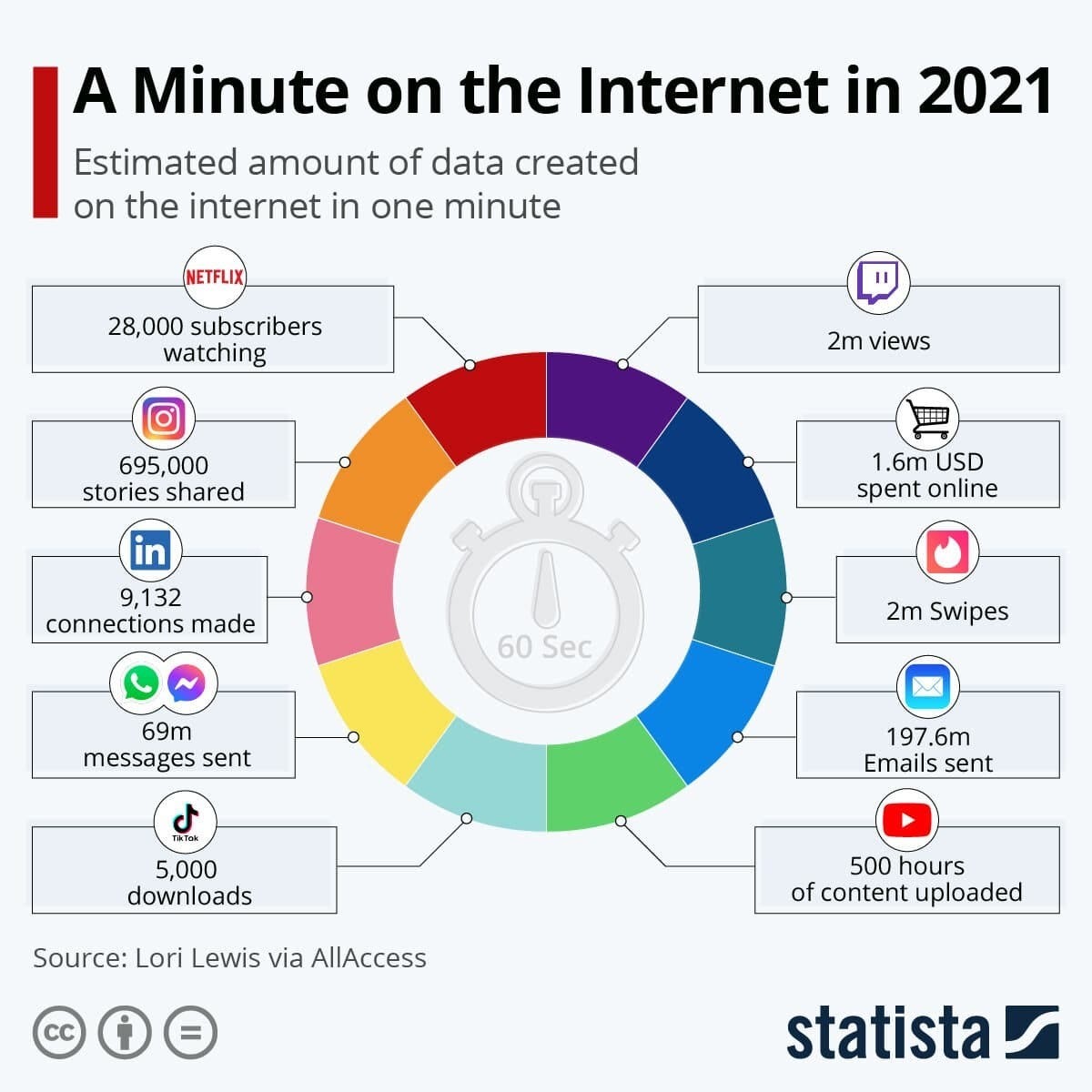

Because of this massive data collection, and the astronomical amount of data generated by users globally, businesses have more ways than ever to harvest precious information about internet users.

Social media, messenger apps, and even your device's software have all become platforms for collecting data. This is largely due to the high value of data in the modern age1, and the high rate of monetization this data offers2. If you're not convinced yet and you want to find out how much your data is worth, check out this handy quiz: https://www.totallymoney.com/personal-data/

Companies often sell or share this information with each other for profit, either through agreements and deals3 or simply for cash. This means that there is a clear incentive for collecting and sharing as much data about you as possible, making your online profiles more accurate and more widely available over time.

This leads to a positive feedback loop, because as companies collect more data, they gain better insights into user behavior. This, in turn, allows them to refine their services, tailor recommendations, and target advertising more effectively. As users engage more with these personalized services, they generate additional data, which adds to your profile, making personalization even more effective.

Section 1: Impacts on Politics and Democracy

How big is the bullseye? Are you getting hit?

Robert Urbaschek, who lives in the Netherlands, has been closely following the Dutch elections and has written two posts explaining the causes of the election upset. We wanted to also mention the Dutch context to illustrate that microtargeting is not only something that happens in the English-speaking world, but rather throughout the global landscape.

In the month leading up to the Dutch elections, which took place on November 22 (with the election period spanning from October 27 to November 25), political parties spent hundreds of thousands of euros on advertising through Meta alone. Interestingly, oil company Shell ranked fourth in total spending (130,625 euros). Other big spenders include Dutch newspaper NRC, Greenpeace Netherlands, Oxfam Novib, Save the Children Netherlands, Amnesty International, Unicef, and energy companies Eneco and Vattenfall. Based on the organizations just listed, it will probably not surprise you that climate and migration policy were big election themes.

After researching the use of microtargeting in the Netherlands, University of Amsterdam scientist Tom Dobber found that just like their U.S. and U.K. counterparts, political parties in the Netherlands use microtargeting, albeit in a different form. He states that microtargeting "isn't such a bad thing in itself," as it can allow politicians to reach citizens with relevant information, as long as they are "acting fairly and in good faith," which he describes as not abusing people's vulnerabilities, and using lies or unlawfully obtained personal data. In the future, he says, advances in technology will only make microtargeting smarter, so its use should be limited to "legitimate players who are acting in good faith." However the other (mainly prevalent) side of the coin can't be ignored, such as the case with data brokers. As mentioned in section 2 from the last post, data brokers unethically collect huge amounts of data about the mass population. This crazy web of data brokerage activities remains hidden from the average person's view. The shadowy world of data transactions and profiling conducted by these companies adds another layer of complexity to the already elusive nature of data influence, which makes it even more difficult to come up with an answer regarding the effectiveness of microtargeting.

Transparency plays an important role in the discussions around the possible impacts of microtargeting on the political process. Similar to more traditional forms of advertising, those with more money and influence will be better able to reach you with their messages. That is why it is important to be aware of how microtargeting affects the information you are exposed to as well as your own decision-making.

So how big are these effects, really? One group of researchers analyzed the effectiveness of different advertising techniques by subjecting different groups of people to varying political messaging strategies. They suggest that there might be a limit on the amount of information that is actually helpful for reaching people with your message. Microtargeting was found to be more effective than more conventional messaging strategies, like using one single message that resonates with the largest amount of people, only when used during single-issue campaigns. For multi-issue campaigns they could not find a significant advantage of microtargeting over using a single message (keeping in mind that it was more effective than showing a random message). Moreover, they found no evidence that using multiple personal characteristics for more specific targeting was of benefit. While this study cannot hope to fully replicate the intricate dynamics of the real world in its simulation, the indication that having more information does not necessarily lead to being able to persuade more people should make us skeptical of any claims made about the effectiveness of microtargeting. Especially because there is a financial incentive on the part of a company like Meta to inflate its ability to influence you to the advertisers it does business with. However, it should be noted that the largest tech companies have infinitely vaster data sets and computing power than these researchers, so they could be using much more accurate information and techniques that can actually give significant advantages for microtargeting. The fact that they are so eagerly implementing AI to make sense of the treasure piles of data they are sitting on clearly shows that at the very least they believe it can be of benefit.

If microtargeting is done well, you will be shown precisely that information that is most likely to sway you, or someone like you. Inherently, this type of advertising is doing the same thing as more traditional ads. Similar to a filter bubble, which is you only seeing the information that you agree with, this personalizing of information could result in the undermining of the basis for a shared public discourse about policies, candidates, the direction of the country, and even reality. In other words, it undermines the very basis of political discussion itself, with each side arguing from within their own reality and not understanding the other side. Meta/Facebook already has a history of experimenting with manipulating users' emotions and targeting people based on psychological vulnerabilities. This raises questions about how independent our thoughts, opinions, and decisions really are, although the same questions can be raised for advertising (and news reporting) in general. When our brains are confronted with lots of information coming at us in a short amount of time (also known as information overload), it is not processed rationally but intuitively, which might lead to "a progression from thought to action artificially."

Section 2: Effectiveness of Microtargeting

Bullseye or bullshit?

Privacy scandals like the Cambridge Analytica scandal have led to more public scrutiny of companies' data collection practices. In recent years, more stringent laws and regulations have been enacted to determine what data can be collected and how it can be used. Political microtargeting violates European laws like the European Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) if it is not done transparently or if it does not give users sufficient control over how their data is used. At the beginning of this year, Meta was ordered to pay a fine by the European Data Protection Board and told to obtain European users' express consent before using their data for behavioral ads. In other words, simply clicking 'agree' on a privacy policy that no one reads does not equal consent. Meta is appealing the decision, and says that the Board's decision does not mean that it can no longer offer personalized ads. This difference in interpretation stems from a GDPR provision that allows for some forms of behavioral advertising. This summer, Meta's legal justifications were struck down by the European Court of Justice, ruling that the company's personalized advertising cannot be justified without user consent. While it is much harder to lawfully obtain people's personal data in Europe, especially when it comes to political opinions, than it is in a place like the United States, these rulings can and do have consequences worldwide. After the GDPR was enacted in 2018, some technology companies decided to apply the GDPR to all their consumers, as a way of saving costs. Incidentally, a side-effect of such comprehensive regulation is that it benefits larger technology providers such as Google, who because of their vast scale and resources can more easily comply with new rules as well as weather legal challenges.

How effective microtargeting is going to be in the future depends on several factors, like how much the ways in which companies can use and analyze your data is regulated, as well as how much people know about how it works. Transparency about what data or techniques are used for showing you an ad could decrease its effectiveness. One study that looked into the effects of ad transparency on their effectiveness found that if a company engages in methods of advertising that people find objectionable or even unacceptable, for instance by not disclosing how they use your information, the effectiveness of the advertising is significantly reduced once users find out. Knowing that you are being microtargeted allows you to evaluate the information accordingly. Interestingly, the study also found that ad transparency had no significant effect on effectiveness if the data collection practices were deemed acceptable. In fact, the higher users' trust in the platform, the more effective the 'acceptable' microtargeted ads are. Of course, the degree to which people are comfortable sharing personal information is highly subjective, can change over time, and depends on the company and types of ads in question. But what is clear is that if these types of regulations become more widespread, companies will have to start taking their users' attitudes into consideration.

At the moment, it is often not clear what information an ad you are seeing is based on, because it remains largely up to tech companies themselves to determine what is and is not allowed on their platforms. A label saying "Paid for by", as Meta is doing now with political ads, might not be enough if the entire content of the message has been shaped based on your personal data. In 2021, the company behind the private messenger app Signal took out a series of personalized ads on Instagram that showed users what information was used to target them with the ad. According to Signal, the goal was to show you what personal data is collected and sold, to highlight how targeted advertising works.

This personal information is being used - on a creepy level - by companies and political campaigns in other contexts to shift individual and collective thoughts into a specific desired outcome, which might not be always oriented towards the public good, and might be driven entirely by selfish motives, power or profit…

— In the next series of posts, we've got an exciting array of content lined up that promises to inform and intrigue you. We’re going to explore how the government and social media companies can contribute to the regulation of microtargeting, as well as what you can do to protect yourself from being influenced and/or manipulated.

We invite you to join the conversation and share your thoughts, insights, and personal experiences in the comments section. If you find this topic as compelling as we do, we encourage you to help spread the word by sharing this post and our Substacks with your friends, family, and followers. We appreciate your readership; stay tuned for our upcoming posts!

These posts take a lot of effort and research to put together. You can show your appreciation by buying me a coffee or by getting a paid subscription!

You can also support Tony’s work by subscribing to his publication and pledging a subscription to let him know that you value his content!

The average revenue per user is estimated to be around $32.03

Where companies sign contracts to share relevant information with each other or use each other's trackers in their respective services

I found those three blue boxes very informative.

A great post! One thing to bear in mind is that just as Meta has a financial interest in inflating their ability to influence, Signal (as well as other privacy-selling companies like most VPN companies) has a financial interest in convincing us of the danger of data harvesting. Now, from what we can tell there *is* a lot of data harvesting, so they're not lying, or even misleading to any substantial extent (probably).

You see this in VPN advertising - so, so many are hyping up their privacy-protection as a primary selling point to 'defeat tracking' (when the actual facts are, so far as I can understand, a bit more mixed). So I wonder how much this is happening in other areas. Apple *definitely* rides this train, and while they are (probably) better than Samsung, they're not as good as they claim. What about Brave? They have a vested interest in me viewing things a certain way. And so on, and so forth.

Again, I'm not saying these companies are necessarily lying, and often we can test their claims empirically. But it's a lot easier to make a claim and perpetuate it than to debunk it, especially if it's not *false* as such, just a matter of emphasis and shading, or hard to empirically detect (like browser fingerprinting).